I grew up in Rochester, New York. For those of you older than 30, you might know Rochester as the home of Eastman Kodak. For those of you younger than 30, Eastman Kodak was the biggest name in film and photography for over 100 years. Obviously, now that everyone and their mother has multiple cameras in their pocket thanks to the smartphone, film cameras have been relegated to the fringes of mass photography.

But the story of Kodak's decline begins earlier, with the sales of digital cameras exceeding the sales of film cameras around the year 2000. It's especially ironic because Kodak invented the digital camera in 1975. This is a well-known case study that's been dissected by institutions such as Forbes, MIT, and the Harvard Business Review. But what I want to talk about is the internal decision-making processes at Kodak that led to the whole thing collapsing.

Much like Rome, Kodak's decline and fall wasn't the result of a singular decision but a series of systemic issues that culminated over time. Kodak was plagued with an internal culture that "regarded digital photography as the enemy, an evil juggernaut that would kill the chemical-based film and paper business that fueled Kodak’s sales and profits for decades" (source: NYT), management that ignored the advice it was given (Kodak ignored internal reports on the future success of digital cameras), and a board that prioritized leaders from profit centers over other areas of the business (multiple CEOs came from Kodak's established business lines rather than from places with differing perspectives).

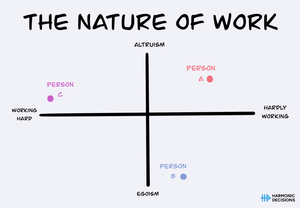

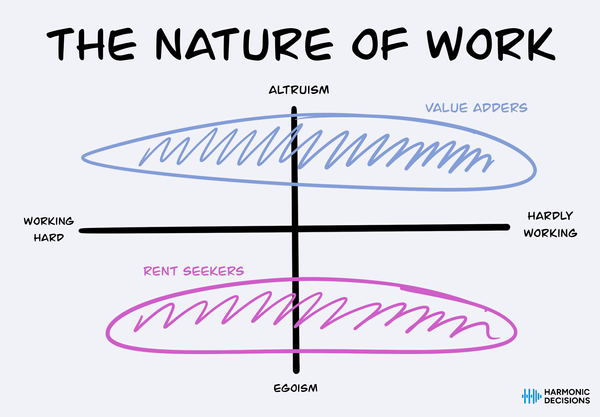

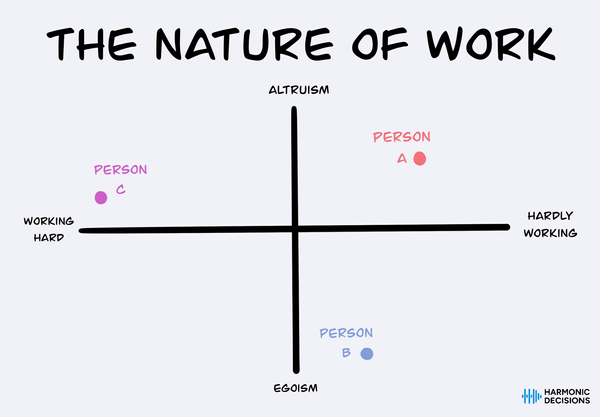

In any business, there are cost centers and profit centers. They are what they sound like: profit centers are those divisions that add to the bottom line, while cost centers are those divisions that subtract from the bottom line. While it seems intuitive to give those people making money for the company a bigger voice when deciding what to do, it's not always the wisest move.

When looking at institutional decision-making, it's always important to understand incentives. Profit centers have an incentive to maintain the status quo. Any change to the business model may destabilize the fiefdom that profit centers have built up, along with the perks and benefits that come with that influence. It's a macro/organizational version of what Ray Dalio calls "the ego barrier" - profit centers build walls around their profits. Executives who come up through the profit centers will often seek to protect and prioritize the divisions that they grew their careers in. The thinking is often, "This was the successful model of the past. Why don't we do more of that?"

To illustrate this point further, I want to look at another Rochester icon: Xerox. While known for printers and copiers, it was also the originator of groundbreaking inventions through its Silicon Valley research center, Xerox PARC. Xerox wanted to focus on its profit center - copiers - and this led to the sidelining of other aspects of its business in ways that hurt Xerox to its detriment. Rather than harnessing the massive amounts of talent it had at its disposal and investing in the technologies it invented, Xerox basically gave away the technology it developed for free. That same technology helped grow companies like Apple and Microsoft into the titans they are today, while Xerox is no longer the household name it used to be.

A more modern example of a company that's consistently deprioritizing business lines that aren't explicitly profit centers is Google. Google is known for search, but it's really in the advertising business. They also dabble in other areas of the internet, among which was Google Domains, their service for buying website domains.

Google Domains was sold to Squarespace in June 2023. This move was not well received by Google's customers, who saw it as another example of the company shuttering products with high satisfaction. The reason for the sale was the profit margin: it simply wasn't making enough money relative to the other areas of Google's business. It was still likely making a profit, but some "napkin math" from The Pragmatic Engineer puts the profit margins of Google Domains at around 10%, compared to the 20-30% on the rest of the business. That difference doesn't seem like much, but it was enough during a time of declining profits to prompt a change.

This post dealt with understanding profit centers. In the following posts, we'll talk about cost centers and how to harmonize their different incentives.

Member discussion