I went to see Dune 2 in theaters, which was the first time I was in a movie theater since, well, Dune 1. Dune 2 was an excellent movie that I'd highly recommend watching, especially since it's one of those rare sequels that's far better than the first installment, but the movie wasn't what got me thinking after I left the theater. What stood out to me from my trip to the movie theaters was my experience at the concession stand - it really struck me how popcorn pricing is a great way to understand the decoy effect.

Ideally, if a movie theater has three sizes of popcorn, you'd expect them to be priced relative to their sizes. So, assuming the size differences are the same between small, medium, and large, you would assume a small goes for $2.50, a medium for $5.00, and a large for $7.50. Because most people will pick the option in the middle, you'd expect to sell medium most of the time.

However, this isn't actually what happens! Movie theaters often price mediums at a higher price - for example, it might be priced around $6.50. This makes the large popcorn seem like a better deal relative to the medium because it's only a dollar more, but you get so much more popcorn. And who would buy multiple small popcorns when you could buy a single large one? This tactic is a great way to price things in a way that moves more of your highest-value product.

The decoy effect is also known as the asymmetric dominance effect. The idea is that if there is a less attractive option introduced to a series of choices, that less attractive option is the decoy that will ultimately increase the chances that another choice already present is chosen. This is commonly found in pricing, but it also shows up in other situations where choice is important.

In politics, new candidates often appear and influence voters' behavior, thereby taking votes from some of the other candidates. The overwhelming majority of the time, this is detrimental to the candidate whose views match most closely to the new candidate's, as more of that candidate's votes will be taken by this new candidate. One famous example was Ross Perot's third-party bid for President in 2000, siphoning enough votes away from Al Gore to hand the election to George W. Bush.

Another place this effect is found is in negotiations. Rather than presenting only serious proposals A and B, it may be useful to have option C, which is of lower value for the other party on the table. This only works if this lower-value option C has a redeeming quality relative to option B despite being completely overshadowed by option A.

The decoy effect is all about capitalizing on value.

In an ideal world, every choice presented has a similar value-to-cost ratio. However, by introducing an option that has a much lower value-to-cost ratio, people - whether they're small business owners, product managers trying to improve certain metrics, or someone frequently negotiating - can incentivize others to choose other options that are more beneficial for them.

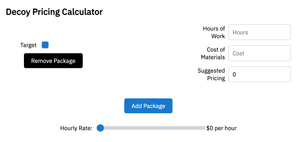

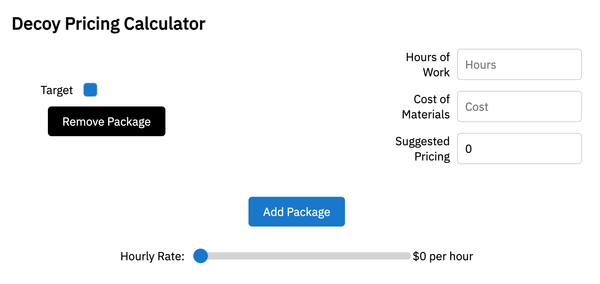

In a world where understanding your own mind and how it operates is one of the best investments you can make, knowing what the decoy effect is and how it works is extremely powerful. If you are one of those people who might benefit from the decoy effect - small business owners, solo creators, people pricing anything - you might like to check out the Decoy Effect Calculator I've built. It'll allow you to input your costs, identify a package you want to sell the most of, and price things accordingly.

Member discussion