The summer after my freshman year of college, I interned at a property management startup. Started by friends I met through Reddit (long story) and documented in the documentary Generation Startup (its apparently on Amazon Prime if you want to check it out), this startup sadly went under some years later. However, as first jobs do, it taught me tons about how I wanted to approach my professional life. When I was on my sabbatical and thinking deeply about the nature of work, I couldn't help but reflect on what I learned then.

The startup I worked for (and the other startups in the house I lived in) was founded by alumni of Venture for America, a non-profit that placed graduates at startups in cities with struggling economies to drive wealth to those cities. If you're a political junkie, you might recognize VFA as the brainchild of former presidential and New York mayoral candidate Andrew Yang. Politics aside, Andrew Yang was highly influential in my life because of the book he wrote outlining his philosophy behind VFA: Smart People Should Build Things.

The book makes the same point its title does but with more data and storytelling. Talented people are often lured to dominant industries and companies by money and prestige. They settle for a life spent collecting rent on these existing structures rather than looking to create value by building things themselves. The benefit of creating value and building things is well-documented by thinkers as disparate as John Rawls, Karl Marx, and Pope John Paul II, who have all elaborated on why meaningful work matters.

Here's one of my favorite quotes from the book, which I think encapsulates the point Andrew wants to convey and the foundation for what I want to talk about: Value vs. Rent.

We need people committed over extended periods of time to creating value, no matter how hard that is. We need people who care deeply about the work they're doing.

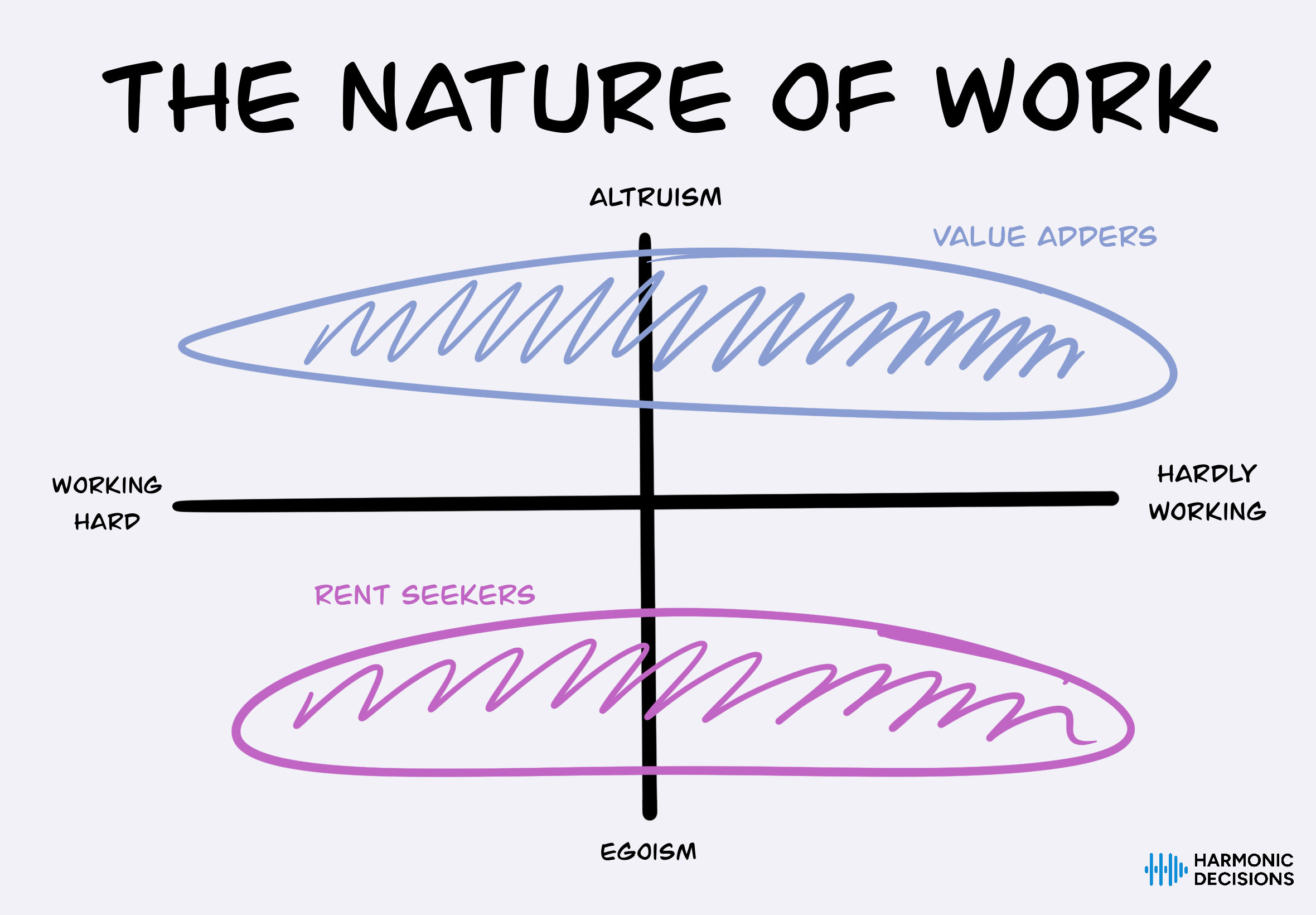

Economists will talk about "rent-seeking" - when people profit from existing structures without contributing anything in return. This is opposed to "adding value," which is when people contribute to those structures. I've touched on this concept before - whether I'm writing about Why People With Money Make Terrible Decisions or explaining the Decoy Effect.

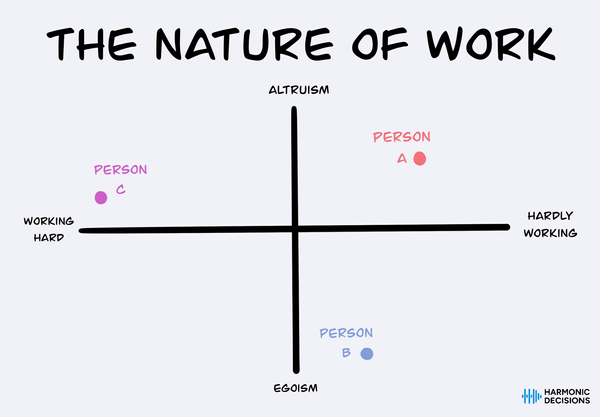

If we were to translate Andrew Yang's point to the nature-of-work framework we looked at last week, we might get something like this:

This is not wrong! Asking, "Does what I'm doing benefit myself or others?" is a great way to get at our internal motivations. If our internal motivations are more egoistic, then it's a fair assessment to say that our value benefits mostly ourselves, i.e., that we're rent-seeking. If our internal motivations are more altruistic, then it's a fair assessment to say that our value benefits mostly others. Exceptions always exist, but this rule of thumb is incredibly useful in assessing ourselves.

The problem appears when we try to use this framework to assess others.

If we wanted to figure out where other people land on this framework, we would need to evaluate two things: HOW they work and WHY they work. Both of those are challenging to do as an external observer.

Most companies try to understand HOW people work through performance reviews. These are often tedious processes and aren't entirely accurate assessments of an employee's contribution. While they may result in roughly accurate evaluations of how well an employee functioned, there's a large variance in outcomes.

The other axis is internal motivation, or WHY people work. Sniffing out other people's true intentions is best left to the psychiatrists, so I won't attempt to understand why others do what they do. And it's precisely this reason that trying to place others on this framework doesn't make sense: we can't get inside other people's heads.

If we try to place people on this matrix, we will judge someone on a single aspect of their identity. We all play multiple roles - someone may be a mother, a manager, a daughter, a sister, an employee, and many other things simultaneously - and we may choose to prioritize one role over the other. What we do in one area of life may seem egotistical, but perhaps not when contrasted with extreme altruism in another.

This is why it's important to note that this framework makes no moral judgments. We may impose our morality on rent-seeking or value-adding, but this again misses the larger picture. Often, people who look to be rent-seekers in one area of life are doing so because they would like to be value-adders in another area of life.

For example, someone may choose a career that requires very little actual effort from their end and contributes very little to the collective benefit of their company. However, financial stability allows them to spend more time with their kids, which adds significant value to their family's lives. A third party who only views this person's professional identity might get the wrong impression about someone who behaves like this. The best course of action, then, is to refrain from using it to assess other people.

Andrew Yang isn't wrong! We need people who care deeply about the work that they do. The issue is that we often try to impose our sense of motivation and priority onto others and, in doing so, flatten their identity. This hurts when it happens to us, but how often do we not think twice about doing this to others?

This framework is powerful because of its personalism. This personalism allows it to be applicable to so many people with differing circumstances in different areas of life. After all, what is most personal is often most universal. Every single one of us will find ourselves in situations where we don't add value, and every single one of us will find ourselves in situations where we do. It all depends on which identity we've taken on at the moment.

Member discussion